All posts in category Institutions

This blog has moved.

Posted by @TomasVH on 26 March, 2014

https://tomasvanhoutryve.wordpress.com/2014/03/26/this-blog-has-moved/

Behind Communism’s Curtain talk at the Oslo Freedom Forum (video and transcript)

I had the opportunity to deliver a presentation about the subject of my book, “Behind the Curtains of 21st Century Communism” at the 2012 Oslo Freedom Forum. The forum brings together an exceptional group of human rights icons, high-level dissidents, artists, journalists and activists (such as modern slavery abolitionists) for several days of talks and meetings. Below you’ll find the video of my 11-minute speech and the full transcript.

• • • • •

Transcript:

Two decades ago, the Soviet Union collapsed and the Cold War ended. Communism, was declared dead.

And many of you will remember that on November 9, 2009 Europe threw a huge party at the Brandenburg gate. World leaders were there, including Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, Hillary Clinton and Mikhail Gorbachev. There were fireworks and one thousand giant dominoes were knocked down to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

On that very same day, I was in a dusty Chinese mountain town known as Yan’an. I watched as dozens of young Chinese actors in historical uniforms reenacted a battle between Maoist revolutionaries and the Kuomintang. In this display, it was the communist forces who were victorious.

Here, a world apart from the events in Berlin, the birth of communism was being celebrated, not its death.

Over the past seven years, I’ve been exploring this world apart with my camera.

It turns out that the areas of our planet where the Communist Party has managed to survive and adapt to the 21st century are far more vast and varied than most of us imagine.

Let’s put it in numbers:

Since the end of the Cold War, the Communist Party has managed to hold power in seven countries across three continents.That’s a total population of 1.47 billion people, with a majority living in China. Or, to put it another way: 1 in 5 people on this planet currently live under Communist Party rule.

And when I sought to take photographs of Maoist revolutionaries during the 21st century, I didn’t need to settle for a historical reenactment.

In Nepal, communist guerrillas following Mao Zedong’s playbook lead a bloody revolution which toppled the country’s monarchy in 2008. 13,000 people were killed in the brutal civil war between the Maoists and the Royal Nepal Army. Thousands of others were disappeared in the middle of the night.

Much of the fighting was a cruel game of cat-and-mouse which played out in remote villages. And it was unsuspecting civilians who bore the brunt of the violence.

Consider the case of this man, Sundar Chaudary, who I photographed in the casualty ward of the Nepalgunj hospital in 2004.

Chaudary spent the first 30 years of his life as a slave. Like his father and grandfather, and one of the other speakers at this forum, Urmila Chaudary, he was born indentured to a high-caste landlord, and he was forced to work 18-hour days.

After years of pressure, Nepal’s government finally acted to ban bonded labor. Eventually Chaudary and thousands of other families were freed of their inherited debts.

He had the chance to start a normal life. He built a modest, thatched-roof home for his family and began to work his own land.

Then one night, a band of Maoist rebels planted a communist flag on Chaudary’s land.

Early in the morning, a patrol of Royal Army troops passed by.

They demanded that he remove the flag. The flag pole was rigged to a mine, and it exploded in his face.

The Maoists considered Nepal’s horribly unjust pecking order as their call to arms. Yet so often their tactics, like building roads with forced labor and conscripting child soldiers, were as harmful as the injustices that they were fighting against.

The communist regimes that I visited during this project revealed time and again how their original pursuit of equality could be abandoned—or maintained as a mere façade—leaving power as an end in itself.

And we should never forget the consequences of totalitarian power. Experts estimate that 20th century communist dictators—including Mao, Stalin and Pol Pot—killed over 85 million people with a legacy of famines, purges and gulags.

North Korea’s Kim dynasty has carried forward their ideology, and its devastating results into the 21st century.

Chillingly, North Korea has managed to do so behind a curtain of total secrecy. When famines struck the Horn of Africa, the international media was filled with images of hungry people and appeals from air organizations.

Yet when famine killed a million people in North Korea, no images made it to the outside world. And North Korean officials kept aid organizations at arm’s length.

North Korea has also managed to keep the world in the dark about its vast system of forced labor camps, which are estimated to hold up to 200,000 people.

In addition to hiding the truth about its human rights abuses, North Korea inundates its own population with hate-filled xenophobic propaganda and paints a god-like image of its leaders.

In North Korea, neighbors and family members are encouraged to spy and snitch on each other to prove their loyalty. The result is a paranoid, militarized society an astounding cult of personality, and the formal absence or any individualism.

By keeping people in the dark about the true nature of totalitarian communist rule the ideology has retained an uncanny popularity over the years.

And many compassionate intellectuals, artists and normal people have cheered on the Communist Party, from Pablo Picasso and Charlie Chaplin to Jean-Paul Sartre and Ernest Hemingway.

For many people exploited by the injustices of capitalism, it has been hard to imagine or remember that another system could be worse.

In 2001, a majority of voters brought the Communist Party back in power through democratic elections in the former Soviet republic of Moldova.

The small landlocked country, which borders the European Union, had struggled to find its footing in the volatile world of global capitalism. Nostalgia for the stability and super-power status of the Soviet Union ran high.

The spell lasted all the way until April 2009, when the Communist Party won another round of elections, although this time they were accused of electoral fraud. Students stormed the parliament in disgust, and they destroyed symbols of the Communist Party.

Fresh elections were organized, followed by period of political instability, until eventually a coalition of pro-European Union parties gained power.

Cuba’s leaders seem equally nostalgic for the past era of Soviet power, and they remain doggedly attached to its model for a centrally planned economy. Despite the poor performance record of this economic model everywhere else in the world, Cuba’s leadership skillfully relies on the stubborn, long-running U.S. embargo as the ideal pretext for deflecting any and all scrutiny and criticism away from the Communist Party’s policies.

But the model that is far more common today is the new breed of state-sponsored capitalism which was perfected by China and adopted by Vietnam and Laos. These countries have embraced the free market, but not in a way that was predicted. High-level Communist Party officials and powerful businesses work together hand-in-glove. The CEO’s of all of China’s big companies in strategic sectors are members of the Communist Party, hand-picked by top officials for their loyalty.

And those capitalist businesses which are boosted with authoritarian steroids perform very well on the global stage, often with the willing participation of foreign investors.

At home, the destructive excesses and inequalities of capitalism now flourish, and without the counterbalances of a free press and independent labor unions. Vocal critics of industrial pollution, mining projects and unfair working conditions are often treated in the same harsh manner as political dissidents by authorities.

When these countries started down the path of economic openness, most commentators predicted that political reforms and progress on human rights would follow.

Those predictions haven’t come true.

Nowhere is that as evident as it is in Laos.

The country’s first stock exchange, which you see here, opened up in the capital last year. A string of glitzy casinos can now be seen near the banks of the Mekong river. But deep in the jungles of Laos, it is as if the Cold War never ended.

There, ethnic Hmong people are living in hiding, constantly in fear of attacks by the Lao People’s Army. Why? Because the Hmong collaborated with French and then American forces during the Vietnam War. After the U.S. was defeated and communist forces took over Laos in 1975, they continued to hunt down the Hmong, a practice which endures to this day.

The Hmong eek out their existence by scavenging for roots in the jungle. They move their makeshift camps every few weeks to avoid detection. When army patrols discover them and open fire, it is often the slowest and the weakest who are gunned down before they can flee into the brush.

For these ethnic Hmong, who still live in the cross hairs of a Communist regime, it would never cross their minds to tell you that communism is dead.

© Tomas van Houtryve 2012. All rights reserved. Do not copy, publish, re-post or archive without the author’s permission.

Posted by @TomasVH on 11 May, 2012

https://tomasvanhoutryve.wordpress.com/2012/05/11/behind-communisms-curtain-talk-at-the-oslo-freedom-forum-video-and-transcript/

Discussing life under Kim Jong Il’s rule with Philip Gourevitch

Earlier this year I sat down in NYC with Philip Gourevitch, a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine, to discuss life along North Korea’s borders. In 2003, Gourevitch wrote Alone in the Dark, a fascinating article which pieces together what life was like under Kim Jong Il.

You can read the transcript of our in-depth discussion, listen to an audio clip and view a slideshow of photos of Korean escapees and the border landscape directly on the Magnum Emergency Fund site. The transcript has also been re-posted below.

TOMAS: So, What kind of picture emerges from North Korea by talking to people who have escaped?

PHILIP: As you’d imagine, people who have escaped don’t have a lot of good things to say about North Korea, but they are pretty convincing about it too. I learned a lot of details about their lives in the North, but also about how intensely resistant the South was to admitting refugees from the North. At that point hundreds of thousands of people had fled North Korea into China from the famine of the ’90s and early 2000s, and only several hundred people had been admitted as refugees into South Korea.

But what you learn about life in North Korea, in almost every case of people I’ve talked to, is that they had been believers. Believers in the North Korean system, in its narrative of imperialist Western aggression, and of South Korea being a terrible American puppet and stooge. In addition to the starvation that had driven them to the border there was an experience that I can only call a kind of explosion of reality in their minds, a profound psychic confusion. North Korean politics is like a religious belief system, structured with the Kims as family deities. To discover everything they ever assumed to be true was wrong and realize everything was upside down, really blew their minds. So the relief of getting out gets compounded with this new retraumatization that had to do with something you don’t get in most refugee situations or just in fleeing hunger–it’s actually a psychic hunger.

TOMAS: And that seems to be true for the people I’ve spoken to fairly recently. They get across the border and all of the sudden they realize that their political system is built completely on lies and their whole world turns upside down. So they think they can work in China for a few months and bring food back, but when they are out there they have this shocking realization. It is already difficult to make their families understand or to decide to make it through to South Korea, which very few do—

PHILIP: That’s right—flight from North Korea is always an extremely difficult decision, for reasons of family, of sheer difficulty of getting out, and also because they believed in it somehow. And then there was the limbo of living in the Chinese border areas, where they were not technically accepted as refugees by the Chinese state and there’s an awkward relationship between Chinese and North Korean authorities. The Chinese had some pity for them, but there was a lot of bribery and corruption and they also liked to have cheap labor they could push around and treat with all the cruelty that illegal aliens anywhere are treated.

Then there’s plopping down in Seoul. And if you’ve been to Seoul you know it like the most hyper-modern city. Everybody’s on their cellphone– and they had no idea how to use a phone or what a push-button device was. It would be as if they were catapulted from the middle of 19th century hermit kingdom Korea into total future-land. And for anybody who was over the age of 25 or 30 there was really a sense that they were a lost generation. They’d been saved from starvation and psychic annihilation in North Korean, but they were never going to catch-up.

TOMAS: I visited North Korea twice—in 2007 and 2008—and was able to see Pyongyang, the DMZ area, and some of the cities close to Pyongyang too. The idea you get of the country is completely different from the border. You go in there, and you realize something is off and they are trying to stage manage something. But you can’t see what is behind. There wasn’t any indication of hunger in Pyongyang, but you can pick up the falsities, the fabrications, that there’s a cult of personality exaggerated to the largest extreme. Going along the border a lot of the pieces started filtering out.

Many of the escapees are women and one of the ways they stay in China is by marrying Chinese men. There is a demographic shortage of women along the border, and North Korea women are considered beautiful.

But it’s quite easy to get denounced and sent back to North Korea, so there’s a population of children who are stateless, born without their birth certificates, who cannot get into school or get healthcare, and their mothers suddenly disappear across the border. Usually the Chinese fathers are poor and give them up, so there are informal orphanages run along the border to deal with these kids.

Along the border, which is mostly a river, the Chinese run tourist operations. There’s a huge curiosity among Chinese, about what’s on the other side. On one occasion on the boat, we came across a North Korean boy hiding in the bushes, gesturing with his hand towards his mouth, “I’m hungry.” The Chinese boat driver had a big bag of snacks to sell to tourists to throw across to the hungry North Koreans. It was very bizarre to be at the gates of incredible suffering, and to know that on the other side, the Chinese who see this as another business opportunity in their bubbling economy.

PHILIP:It sounds like they look at it like a zoo or a nature preserve. They buy snacks to throw across, and you chuckle about their strange ways.

There’s not much on that side of the Korean border, is there?

TOMAS: It’s fairly deforested because they’re using trees for cooking charcoal. Near Dandong, they built showcase houses right along the river to try to face off the Chinese skyscrapers. But the Chinese laugh, and see through this. They say “these are empty homes.” And at night it looks like a medieval village, with only one or two light bulbs in the entire neighborhood – where on the Chinese side there’s LED lights and flashing neon. Basically it looks like the Las Vegas strip.

PHILIP: When you photographed the refugees you didn’t want to show their faces. Do you feel this is something you can convey in pictures?

TOMAS: It was a huge challenge photographically, because their stories are so incredibly powerful, and you are deprived as a photographer of using all of the emotion that a face conveys. I was working with very limited human gestures to bring across what were incredibly powerful emotions and stories. This is one of the most difficult projects I’ve worked on. But the photos are an entry point, and you have to read or listen to the people in the photographs, to get a clear understanding of what is happening.

It’s kind of like being at the gates of Auschwitz and seeing smoke in the distance and one skinny person, but there’s something much more terrible going on. Being on the edge of North Korea makes you see that all indications points to something terrible but you have no direct evidence.

PHILIP: Right, what makes it haunting is knowledge that is not in the picture.

TOMAS: Exactly, but what you can tell from the pictures is that compared to ethnic Koreans living in China for a long time or to South Koreans, North Koreans are much shorter, and the skin on their faces much tighter and wrinkled. You could see they have had really hard lives. Even officials who should’ve been part of an elite looked like they had been working in the sun on minimum food. They have been hardened. If you compare that to the Chinese today, getting plump in the boom of this consumerist economy, the short, more tanned, wrinkled North Koreans stand out.

PHILIP: Yeah that’s what I remember from seeing pictures from the defectors of when they defected. And frankly, they looked like toy people next to the Chinese who aren’t huge to begin with. Right, I mean they aren’t towering people. But then you have these people who look mummified, like shrunken versions of themselves.

When I met people in or around Seoul they were not worried about being seen but even still, it was hard for some to talk. How available were they to you and how guarded were they once they opened up?

TOMAS: You could tell they were uncomfortable, initially. I’d work through various intermediaries and translators before they’d gotten to me, and these people had done interviews over the years for other journalists or human rights organizations. Initially they would be suspicious, then you would get some real information, and then you would have to be careful because they seemed to be telling you information that would please you. It was a delicate balance of feeling out how much you can trust of what they say. Inside Pyongyang the kind of propaganda about Westerns is just incredible and insane. I was taken to a museum that had a picture of a priest and a doctor torturing a baby with hot irons, and they said, “This is an American priest and doctor.” So when they come out and see a Western face for the first time, they must have all kinds of emotion that come up.

PHILIP: Yeah, I would imagine. It’s because they are in that limbo again. They want help, and want people to say “wow this is one of the worst cases I’ve ever seen.”

TOMAS: We had to make it clear to them, no matter how terrible their story we were there just to transmit their story. And we weren’t there to give handouts to whoever had the more horrible experience in life.

PHILIP: Well it’s a bit puzzling for people to deal with journalists like that. Like, “are you a lawyer, can you help me, will you get me a visa?”

TOMAS: And sometimes you don’t know what the intermediaries had said. They were taking big risks to be photographed and speak with journalists. Chinese can get a bounty if they catch North Koreans. And North Koreans get rounded up all the time. For those who get sent back, they get the harshest treatment: forced labor camps and torture. There’s also collective punishment: if one North Korean does something wrong, the whole family is punished.

PHILIP: Now the Chinese are trying to balance not allowing everybody to come, and not a total crack down either, because they would be perfectly capable of sealing that border or policing their side quickly and sending many more people back.

TOMAS:There is a change, now the Chinese have added a lot more surveillance. And from stories, it seems like getting across is much more difficult than it was 5 or 10 years ago.

But I actually encountered two people who had gotten visas to come to China. One of them was from the elite and was given a visa to set up a business transaction. He couldn’t get it through in time, so he overstayed his visa, thinking that if he could pull off this business deal, North Korean officials would forgive his overstay. He was very interesting, because he knew what was going on, he pierced through this veil of falsity. But on the other hand, he was constantly justifying the government’s actions, saying that the government does this because of natural disasters or this and this pressure.

There was another person who had a relative in China. And once she got out her whole world fell apart, so she decided to overstay her visit.

But now smugglers are involved in the process, you have to pay a lot of money to someone who knows the exact crossing points or can bribe guards watching the border. A lot of the people getting out now are relatives of South Koreans who have made it all the way to Seoul, started to integrate, saved money and then sent tons of it back to these smugglers to bring people across.

PHILIP: You had some photographs of a bridge, where is it? Who crosses that bridge?

TOMAS: This is a bridge going from Dandong to the city on the Korean side, Sinuiju. A few trucks and a train cross once or twice a day. This is right next to another bridge bombed during the Korean War that was left up as a monument to the war. There is a little bit of trade. But when you consider 20 million people on the North Korean side, the trade is just miniscule. For a population the size of California, there are maybe 50 trucks crossing a day.

We asked the people on the North Korean side about the famine and the shortage of goods, and they said there were a lot of Chinese goods on the informal markets, but nobody can afford them.

In the mid ’90s, after the Soviet Union collapsed and other countries were helping and propping up North Korea, the planned economy and the internal food distribution system fell apart. People didn’t know how to cope with that. From one day to the next paychecks and food distribution stopped and many people died. The generous people died first, because they wouldn’t eat to help the elderly and sick. Now, that same “falling off a cliff” famine couldn’t happen anymore because people have gone through 20 years of figuring out how to make ends meet through illegal ways if needed. All the North Koreans repeated: “we’ve learned how to live. We’ve learned how to survive.” So when the factory pay checks or the food distribution stop, they know how to trade things, how go to the market. Things that would’ve been really illegal in the 1990s are more tolerated now, like making cookies in your house and selling it to neighbors.

PHILIP: I remember in the famine of the ’90s, there was this characteristically lunatic North Korean central planning of agriculture, and at that moment, Kim Il-sung had this idea that everybody should grow corn – which was the wrong crop – and it becomes this “He Says Grow Corn.” So everybody grows corn everywhere—on steep sides of riverbanks—and then it rains. The entire food supply gets washed away and everybody dies of hunger.

TOMAS: Now there are secret gardens in the forest, behind apartment buildings. And in this black market economy there are people doing quite well. One story people told me is that trains in North Korea constantly break down. And there are people who constantly ride trains with things to trade because they know people will run out of food. So, there’s this guy that prepares food, and waits for it to break down. People get hungry after three hours, and the guy gets every body’s watches and shoes, and gives everyone meals. There are people whose profession it is to find holes in the system.

PHILIP: This must be pretty much the only country in the history of countries that brutalize their own in various different ways, that has really sought to prevent people from being able to feed themselves. It’s not normally considered a good way of controlling people.

TOMAS: In the past, South Korea, the United States and the United Nations have given food to North Korea. Should that continue? Does it get to the people in a system where food is used to control people? They seem to confirm that food meant for the most vulnerable ends up getting diverted to the military. And people accept that, they say, “We’re on the verge of war, so we need to have the military strong, otherwise we’re going to be steam-rolled by the Americans or the Imperialists.” But they also plead and say “Please keep sending the food even if it gets diverted to the army, we all have relatives in the army and somehow it will trickle down to us eventually.” It’s a very tough and nuanced decision: if you give food to North Korea, there’s no way to verify it’s going into the hands of the hungry, but if you give lots of food to North Korea, some of it will eventually spill over to the hungry.

PHILIP: Right, it is a very strange situation that we’re propping up and helping to sustain a regime that by all rights we should be trying to strangle to death-we should be trying to starve it.

But everyone is always wondering, because surely one day North Korea has to crack in some direction and break open. The idea has always been, that there will be reintegration with South Korea and it will be a burden. The South Koreans are extremely ambivalent about reintegrating with the North Korea.

For the first decades after the Korean War, the rhetoric was just “reunification”, but then they saw Germany and realized how expensive this could be. The sheer price per head basically. Now, East Germany looks like Shanghai compared to North Korea, so it’s going to be much more expensive and much more complicated. The adult population isn’t going to integrate logically into a modern state. So they are working against terrible human deficits in every sense. Then the Chinese seem ready to flow in there, and at least do border trade, develop it and buy assets – and also to keep them from becoming entirely Westernized.

TOMAS: As it is right now, North Koreans do try to attract a certain number of Chinese. But the Chinese has had it, and don’t want to do business with them anymore because they’ve been burned so many times. They feel like the North Koreans have been opportunist and not straight-dealers. For example, they’ll allow factory equipment and investment in, but suddenly they’ll start blocking the visas for the businessmen and not following through on their contracts. There was a thirst among the Chinese, seeing North Korea as untapped, undeveloped, full of business opportunities. But the Chinese these days feel very hesitant, they are really not interested in doing business with the North Koreans.

PHILIP: It is such a strange story isn’t it? I mean, there are a lot of regimes that are brutal to their people. But they have a kind of logic; you can understand it even if you can’t relate, accept or approve it. None of the above apply to Pyongyang. You would imagine that the Pyongyang elite would realize what a crummy deal it is to be a Pyongyang elite, and start wanting to say, “Why don’t we start liberalizing trade with China and then we will become really rich Pyongyang elites so that one day when the system falls apart we will be one of the 50 richest people in North Korea?” But they don’t even do that! It’s just weird.

TOMAS: It just seems like they have stoked and leveraged the worst of every political system ever on the face of the Earth: they use the religious dynasty-based loyalty to the “Supreme Leader” and the absolute destruction of the individual you can have in communist societies. Then there are right-wing tendencies, like nationalism and racist pride. They have become so isolated from the rest of the world that they don’t want to bridge the gap even if it’s in their economic interest. They would rather go hungry before dealing with the outside world.

PHILIP: It’s a very paranoid mentality. Now, the Chinese are sitting ther; they are looking across the border at this. Do they have any identify with North Korea? Do they say, “Not so long ago, before we loosened up a bit, we were in that kind of state”? Is there any identification, memory, or sympathy?

You have a picture of Chinese tourists on the beach with their little dog, colorful hats and umbrellas, and this could be on the Italian Riviera. But on the background is one of these barren hills of desolate North Korea. It’s like picnicking by a gulag fence. What do they think?

TOMAS: Those Chinese people living on the inside of the country don’t know what life is like in North Korea at all. Chinese press isn’t free enough, there’s not enough reporting on North Korea for the average Chinese person. But the ones on the border all seem to know.

PHILIP: You would have to wonder if you were sitting looking across the river. They have got to think, “There is another country over there and the country is dark.”

TOMAS: But they do know. They say “They have nothing, just like we had nothing. They live like we did in the 1950s.” I went on a Chinese tour group in a bus where you had a local, snappy, smart teenage tour guide who lives along the river basically mocking the North Koreans, saying “Look how poor they are, we used to be like that.” And the people kind of chuckled along: “Those silly North Koreans over there.”

From what we can learn about North Korea, what does it mean for its neighbors and the United States. Can we negotiate with North Korea? It’s not the first communist or totalitarian country that has popped up, how should we deal with it?

PHILIP: It is the most sealed off. I remember in the late 80s West Germany talked about this geographical region in East Germany that couldn’t get the radio or television signals, and even other East Germans referred to it as The Valley Where They Have No Idea. All of North Korea is like The Valley Where They Have No Idea.

One of the puzzling things is that you have this highly Westernized, Western oriented, anti-communist South, and China, as its two bordering countries. Both have very strong reasons for not wanting North Korea to go away. The Chinese don’t want to lose this last puppet government with military value. China looks pretty good when it can always point to its crazy cousin waving missiles around and say “listen, we are pretty well behaved here.”

Are they capable of launching a missile it into the air and hitting a target? Nobody fully believes they could do it, but nobody wants to find out. There’s always been a hostage situation in both directions. North Koreans are held hostage by their government and by the world’s unwillingness to help. Nobody has an overwhelming interest to see what happens after it’s gone. On the other hand they’re holding the world hostage by having about 13,000 artillery pieces aimed straight at Seoul from 12 miles away–which is an unbelievable hostage situation. “One false move and we blow up Seoul.” Nobody seems to believe it’s all bluff, right? And they are a little crazy.

I got a feeling that everybody was just hoping that it wouldn’t happen on their watch, that nobody knows what to do about it – which is bizarre because at its core one has to believe that this regime is unbelievably weak, that it doesn’t command the loyalty of a starving people, that the starving people aren’t capable of defending it, that although it has a few modern weapons, to a large degree, it’s in the stone ages, technologically.

TOMAS: The only thing that is keeping it in check is this myth. So the army may have old and outdated weapons, the food supply may have fallen apart, the economy may be in tatters—all markers you would typically use to predict a solid state collapse—but the myth is perfectly intact. People still believe that they are special, from the chosen country, and are surrounded by enemies on the brink of war.

PHILIP: And this is where we come in. You would think journalism of some kind or story-telling is what usually makes a big difference, when a totalitarian myth loses its totality.

Every one of the defectors that I spoke to in South Korea had a moment of: “Oh, wow, it’s not like they said it is out here.” And then they come back and they’re mad and confused so they build their own little radios. The most subversive thing that you could do would be to get radios into that country. I know during the Rwanda genocide there was talk of scrambling the radio stations since they were being used as a means of control. Couldn’t we put a satellite over this country and more or less switch the channel?

But we don’t want to! We’re terrified of what could happen. This is like another planet or we have this other planet on our planet. So we’ve got to surround it, and we think “Oh shit, what happens if it breaks open, or if we break it open?” Will it attack us? Will it cost us too much? So let’s just leave it there.

• • •

Also, it’s worth checking out Gourevitch’s latest post, Unreality Check: From Kim to Kim in North Korea on The New Yorker blog.

Posted by @TomasVH on 20 December, 2011

https://tomasvanhoutryve.wordpress.com/2011/12/20/discussing-life-under-kim-jong-ils-rule-with-philip-gourevitch/

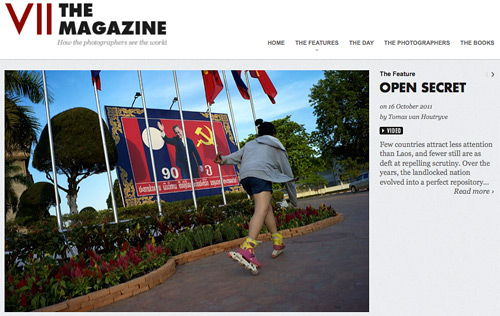

Laos | Open Secret multimedia in VII The Magazine

The latest incarnation of my Laos | Open Secret photo project is featured with sound and video in VII The Magazine. The multimedia was edited by Scott Thode.

If you’ve been following this project, you’ll know that it would not have been possible without the support of 140 individuals through the Emphas.is crowd-funding platform. The International Rescue Committee is also supporting this work and helping to get the word out about the situation in Laos by distributing Open Secret mini-books.

If you would like to help raise awareness about the treatment of the Hmong in Laos, please actively share the multimedia link or contact me to order bulk copies of the mini-books for distribution.

Posted by @TomasVH on 23 October, 2011

https://tomasvanhoutryve.wordpress.com/2011/10/23/laos-open-secret-multimedia-in-vii-the-magazine/

You must be logged in to post a comment.